The Golden Years Care Facility smelled of bleach, wilted roses, and quiet despair. For thirty years, I’ve been a nurse, and I’ve learned that every long-term care facility has its own particular scent of sadness. Here, it was the smell of erasure. We were a place where memories came to fade, where vibrant lives were condensed into a few faded photographs on a bedside table and a list of medications on a chart. And for the past two years, my most heartbreaking case of erasure was Harold Morrison in Room 247.

Harold was eighty-nine years old, a veteran of the Second World War, and a ghost who haunted his own life. His family, a distant nephew who paid the bills but never visited, had dropped him here and disappeared. Harold spent his days parked by his window in a wheelchair, his body a frail, shrunken vessel, his eyes fixed on the birds flitting between the manicured trees on the lawn. He was forgotten, and he knew it.

But Harold had a secret. I’d pieced it together from the rare moments when the chemical fog of his sedatives would lift. He would talk about the open road, the thunder of an engine between his legs, and his “brothers.” He’d speak of a cross-country ride in ‘48, of a bar in Sturgis, of designing a patch himself—a snarling horse with devil horns. They were, to him, the most vivid memories he had. To the facility’s director, Mrs. Chen, they were the dangerous delusions of a senile old man. Every time Harold got agitated, every time he mentioned wanting to feel the wind on his face one last time, his file would be updated. “Patient exhibits combative nostalgia. Prone to agitation.” A quiet order would be given, and his dosage of antipsychotics—a chemical restraint disguised as a relaxant—would be increased. I watched him fade a little more each day, his stories growing fainter, his eyes growing glassier. It was a slow, methodical murder of the soul, and it was breaking my heart.

The day it happened began like any other Tuesday. The quiet hum of the floor polishers, the clatter of lunch trays, the droning of a game show on the television in the common room. And then, the sound began. It was a low rumble at first, a distant vibration that I felt more in the soles of my orthopedic shoes than in my ears. But it grew, and grew, swelling into a thunderous, ground-shaking roar that rattled the windows and made the residents’ water glasses tremble.

I rushed to the front lobby just as they began to pull in. Forty of them. Forty massive, gleaming motorcycles, a tidal wave of chrome and black leather that filled the entire parking lot. They moved with a disciplined, intimidating grace, parking their bikes in perfect, menacing rows. The patches on their vests were unmistakable, an image I knew from Harold’s whispered stories: the snarling horse with devil horns. The Devil’s Horsemen MC.

The front door opened, and the man who entered seemed to suck all the air out of the room. He was a mountain, well over six feet tall, with a braided gray beard that reached his chest and arms covered in a roadmap of faded tattoos. He moved with a quiet, unshakeable authority, his biker boots thundering on the polished linoleum. A dozen more of his brothers filed in behind him, filling the lobby with the smell of leather, gasoline, and the open road. They didn’t speak. They just stood there, a silent, leather-clad army.

Our receptionist, a young woman named Brenda, looked like she was about to faint. Her hand hovered over the panic button beneath her desk.

“Where is he?” the big man demanded, his voice a low, controlled rumble that was somehow more intimidating than a shout.

“Sir, visiting hours are over,” Brenda stammered, her eyes wide with terror.

“Harold Morrison,” the man said, his gaze as hard as granite. “Room number. Now.”

That’s when Mrs. Chen emerged from her office, her face a mask of pinched indignation. “I’m calling the police,” she announced, her voice shrill. “We have a strict policy. We don’t allow gang members in this facility.”

That’s when I should have kept my mouth shut. I should have blended into the background, protected my job, my pension, my quiet life. But all I could see was Harold’s face, the vacant look in his eyes as he stared out that window, waiting for a death he thought would be his only escape. I thought of the stories he’d told me, the flicker of the young, wild man that still lived somewhere inside that frail body. And I knew these weren’t gang members. They were ghosts from his past, come to answer a prayer he’d long since forgotten how to speak.

“Room 247,” I said, my voice ringing out with a clarity that surprised even me. “Second floor, end of the hall on the left.”

Mrs. Chen whirled on me, her eyes blazing with fury. “Nancy! You’re fired!”

A strange sense of liberation washed over me. “Good,” I shot back, the words tasting of freedom. “I’m tired of watching you drug old people for being inconvenient.”

The bikers were already moving. They flowed toward the stairs like a single organism, their boots a thunderous heartbeat on the steps. My own heart was pounding as I followed them, a strange mix of terror and exhilarating hope surging through me.

What happened when they opened Harold’s door would become the most beautiful and heartbreaking scene I would witness in my thirty years as a nurse. The big man, their leader, didn’t kick the door down. He pushed it open with a quiet, almost reverent push.

The room was just as I had left it that morning. Harold was in his wheelchair, positioned by the window, his back to us. He was painfully thin, his skin like tissue paper wrapped around a bird-like skeleton. The sedative haze was thick around him; his eyes were vacant as he stared at the sparrows on the bird feeder outside. He didn’t even turn around. The hope in my chest faltered. Maybe we were too late. Maybe the man they were looking for was already gone, leaving only the shell behind.

The big biker, a man who looked like he could wrestle a bear, took a hesitant, almost timid step into the room. The other bikers filled the doorway behind him, a silent, leather-clad honor guard, their massive frames seeming to shrink in the presence of this frail old man.

“Harold?” the big man said, his voice softer and more vulnerable than I could have ever imagined a man’s voice could be. “It’s Mike. Big Mike Stern. We’re here, brother.”

Harold turned his head slowly, the movement stiff and labored. His eyes were cloudy, unfocused. He looked past them, through them, his gaze lost in the fog of the medication. My heart sank. It was over.

But then, his gaze drifted down, down to the patch on Big Mike’s vest. His eyes, for just a fraction of a second, locked onto the Devil’s Horsemen insignia—the very one he had sketched on a cocktail napkin in a dusty California bar in 1947. A flicker of light, a tiny spark of recognition, appeared in the gray depths. His frail, trembling hand lifted from his lap, his fingers reaching out, questing.

Big Mike was on his knees in an instant, the sound of his knees popping echoing in the silent room. He brought his broad chest level with the old man’s hand. Harold’s finger, gnarled with age and arthritis, traced the stitched outline of the snarling horse he had created a lifetime ago. A single tear escaped his eye and traced a slow path down his wrinkled cheek. His lips parted, and a dry, raspy whisper, the sound of dust and disuse, filled the sacred silence of the room.

“Ride Forever…” he breathed, the first two words of the club’s sacred motto.

The biker standing next to me choked back a sob. Big Mike finished the phrase, his own voice thick with an ocean of emotion. “…Forever Free, old friend.”

The legend was still in there. The king had not abdicated his throne.

“We’re taking you home, Harold,” Big Mike said, his voice now firm with a renewed, unshakeable purpose. Without being asked, I ran to Harold’s closet and pulled out the one personal item his family had bothered to leave: his original, worn leather jacket. The leather was cracked and faded, but it still smelled faintly of oil and the open road. They slipped it over his frail shoulders, and it hung on him like a royal robe.

When we got back to the lobby, Mrs. Chen was there, flanked by two uniformed police officers. Her face was a triumphant sneer.

“This is kidnapping!” she shrieked, pointing a trembling finger at us. “This man is a resident of my facility! He is not medically cleared to leave!”

Big Mike didn’t even waste a glance on her. He addressed the officers directly, his demeanor calm and respectful. He pulled a thick envelope from the inside of his vest. “Officers, my name is Michael Stern. This is the phone number for our lawyer. Inside this envelope, you will find a notarized and legally binding power of attorney, signed this morning by Harold’s only living relative, his grand-nephew in Seattle, granting us full medical and legal guardianship of Harold Morrison.”

He then looked at me. “You will also find a signed and dated affidavit from Nurse Nancy here, testifying to the improper and punitive use of chemical restraints on Mr. Morrison by this facility’s director.”

The officers looked from the papers to me. I met their gaze, my own voice clear and strong. “It’s true. They drug him every time he gets agitated about wanting to go outside. They call it agitation; I call it a man wanting to live. It’s abuse.”

The cops’ expressions changed instantly. They were no longer looking at a biker gang and a hysterical director. They were looking at a rescue mission. One of them nodded curtly at Big Mike and then took a half-step back, clearing a path to the door.

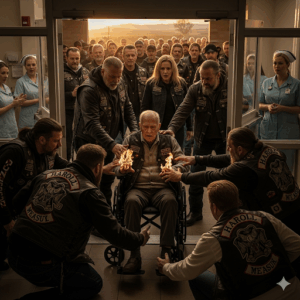

The bikers carried Harold, wheelchair and all, out into the bright, beautiful sunshine. He lifted his face to the sky, and a real, genuine smile spread across his lips for the first time in the two years I had known him. At the curb, a beautiful, vintage motorcycle with a gleaming black sidecar was waiting. They gently lifted Harold from his chair and settled him into the sidecar, wrapping him in warm blankets and placing his old, cracked riding goggles over his eyes.

Big Mike started the engine, and a deep, soul-shaking roar filled the air. He looked back at Harold, his own eyes shining. “Ready for one last ride, old man?”

Harold couldn’t answer with words, but the joyful, peaceful, utterly liberated look on his face said everything.

He didn’t die in that sterile room, forgotten and sedated, staring at the birds. Harold Morrison lived for three more months. He lived at the clubhouse, in a room they had converted just for him, surrounded by the rumble of engines and the laughter of his brothers. Free from the sedatives, his mind grew sharper than ever. He spent his days on the porch, telling stories of the club’s founding, of long-lost brothers and legendary rides, his voice growing stronger each day. He was no longer a ghost. He was a king, rightfully returned to his throne.

When he passed, it was in his sleep, with the smell of leather and gasoline in the air and the sound of his brothers’ laughter outside his door. He died a Devil’s Horseman. He died free.

As for me, I never went back to Golden Years. I’m now the resident nurse for the Devil’s Horsemen MC. My practice is run out of a small office in the back of the clubhouse. I patch up scraped knuckles, check blood pressures, and listen to more stories than I can count. Because I learned that day that family isn’t just about the blood you share. It’s about the people who, when you are lost in the darkest hell, ride back in and pull you out.